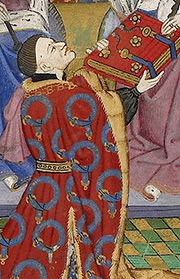

ritten by William Shakespeare in 1599, these lines, — Henry V, iv, iii, 18–67 — are delivered to some disspirited English soldiers by King Henry V (painting at right by an unknown artist, National Portrait Gallery, London) on the night before the Battle of Agincourt, October 25, 1415, during the Hundred Years’ War, 1337–1453. Although outnumbered by an army of 30,000 led by armored and mounted French knights, the English at 5,000 won the battle the on following morning. (Painting below from an illuminated manuscript.) The night before the battle, the soldiers wish that they had more men to fight with them. Henry’s cousin Westmorland agrees, O that we now had here / But one ten thousand of those men in England / That do no work today! Henry, who has been listening unnoticed, interrupts them and replies to what he has overheard, declaring that they have enough men to make history.

What’s he that wishes so?

What’s he that wishes so? Who wants more men? The word what is often used apparently with no sense of what kind or quality. The answer seems to show a measure of indefiniteness in the question.

My cousin Westmoreland? No, my fair cousin;

If we are mark’d to die, we are enow

Henry’s cousin Ralph Neville, first Earl of Westmorland (1364–1425) helped incite the king to war against France. He also appears or is mentioned in Henry IV, Part One; Henry IV, Part Two; and in Henry VI, Part Three. Although the king addresses him in this speech, Westmorland was actually not at Agincourt. At left, detail of his effigy at Staindrop Church, County Durham.

enow, Old English variations genoh, ynough, ynow, enow, anow, ynough, enow, and anow, are to be found throughout Elizabethan literature.

To do our country loss; and if to live,

The fewer men, the greater share of honor.

God’s will! I pray thee, wish not one man more.

By Jove, I am not covetous for gold,

Nor care I who doth feed upon my cost;

who doth feed upon my cost, who profit at my expense

It yearns me not if men my garments wear;

It yearns me not, it does not annoy me

Such outward things dwell not in my desires.

dwell not in my desires, do not preoccupy me

But if it be a sin to covet honor,

I am the most offending soul alive.

No, faith, my coz, wish not a man from England.

God’s peace! I would not lose so great an honor

As one man more methinks would share from me

For the best hope I have. O, do not wish one more!

my coz, my cousin Westmorland

would share from me, would take away from me

O, do not wish one more!, not one more man

Rather proclaim it, Westmoreland, through my host,

That he which hath no stomach to this fight,

That he which ... That he who has no courage for this fight

Let him depart; his passport shall be made,

And crowns for convoy put into his purse;

passport shall be made, return to Englnd will be secured

crowns for convoy, travel pay

We would not die in that man’s company

That fears his fellowship to die with us.

We would not die in that man’s company, We would not die in the company of any who fear to die with us

This day is call’d the feast of Crispian.

Feast of Crispian The battle of Agincourt was fought on October 25, 1415. The saints who gave name to the day were Roman-born brothers Crispin and Crispianus, who travelled to Soissons in France in about the year 303, to propagate Christianity. There they worked as shoemakers. The governor of the town discovered them to be Christians and ordered them beheaded. Hence they became the patron saints of shoemakers. The vigil is the evening before the feast. Image, detail, Aert van den Bossche, 1491, Martyrdom of Saints Crispin and Crispinian, Museum of King John III's Palace at Wilanów, Warsaw

He that outlives this day, and comes safe home,

Will stand a tip-toe when this day is nam’d,

Will stand a tip-toe, will be very proud, exult, when the battle is recalled

And rouse him at the name of Crispian.

He that shall live this day, and see old age,

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbors,

And say “To-morrow is Saint Crispian.”

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars,

And say “These wounds I had on Crispian’s day.”

Old men forget; yet all shall be forgot,

But he’ll remember, with advantages,

What feats he did that day. Then shall our names,

vigil, the eveof the aniversary of the battle

But he’ll remember, with advantages ... He will exaggerate the feats he performed on that day.

Familiar in his mouth as household words,

Harry the King, Bedford and Exeter,

Warwick and Talbot, Salisbury and Gloucester,

John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford (1389–1435), commanded England's armies in France during a critical phase of the Hundred Years’ War. Bedford was the third son of King Henry IV, brother to Henry V, and acted as regent of France for his nephew Henry VI. Detail from a manuscript page by the French painter known as the Bedford Master.

John of Lancaster, Duke of Bedford (1389–1435), commanded England's armies in France during a critical phase of the Hundred Years’ War. Bedford was the third son of King Henry IV, brother to Henry V, and acted as regent of France for his nephew Henry VI. Detail from a manuscript page by the French painter known as the Bedford Master.

Thomas Beaufort, Duke of Exeter (1377–1426), military commander during the Hundred Years' War, and briefly Chancellor of England. He was the third of the four children born to John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, and his mistress Katherine Swynford. Pictured, the duke’s arms.

Richard Beauchamp, 13th Earl of Warwick (1382–1439), successful military commander, knighted by Henry IV, and trusted counsellor to Henry V. He took a prominent part against the French in the campaigns of 1417–18. Then he joined the king before Rouen, and in October 1418 had charge of the negotiations with the dauphin Louis and with the duke of Burgundy. He went on to hold high command at sieges of French towns between 1420 and 1422, and he acted as superintendent of the trial of Joan of Arc in 1431. Drawing of Richard holding Henry VI from the Rous Roll, c. 1483.

John Talbot, First Earl of Shrewsbury, First Earl of Waterford, seventh Baron Talbot (1387–1453), he was the English commander most renowned in England and most the most feared in France in the last stages of the Hundred Years’ War. Known as a tough, cruel, and quarrelsome man, Talbot distinguished himself militarily, and is lavishly praised in the plays of Shakespeare. (Henry VI Part One, i,v) The manner of his death, leading a charge against field artillery, has come to symbolize the passing of the age of chivalry. Image, detail of illuminated miniature from the Talbot Shrewsbury Book, 1444–5.

Thomas de Montacute, fourth Earl of Salisbury (1388–1428). His father, the third earl, was executed in 1400 as a supporter of Richard II. He was at Agincourt, at the naval engagement before Harfleur in 1416, as well as many other engagements throughout France. When Henry returned to England in 1422, Salisbury remained in France as the chief lieutenant of Thomas, duke of Clarence, then as John of Bedford’s chief lieutenant after Henry’s death. He died from canon fire during the siege of Orléans.

Humphrey of Lancaster, Duke of Gloucester (1390–1447), fourth and youngest son of Henry IV, brother of Henry V, and the uncle of Henry VI. Gloucester fought in the Hundred Years’ War and acted as Lord Protector of England during the minority of his nephew. A wounded Gloucester was is said to have been protected by Henry from a French assault. Image, 16th century drawing based on a contemporary portrait (from the Recueil d’Arras)

Be in their flowing cups freshly rememb’red.

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne’er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remembered.

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne’er so vile,

be he ne’er so vile, be he ever so low-born

This day shall gentle his condition;

This day shall gentle his conditions, This day shall advance him to the rank of a gentleman. It has been asserted that Henry prohibited any person who had a right by inheritance or royal grant from bearing coats of arms, except those who fought with him at the battle of Agincourt. These veterans were allowed the chief seats at all feasts and public meetings.

And gentlemen in England now-a-bed

Shall think themselves accurs’d they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

hold their manhoods cheap, be ashamed of themselves when any of our fellows recalls the battle

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin’s day.